Billboards, broadsides, and signage in Thomas W. Kennedy glass plate negatives

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

July 30, 2020

During the quarantine of 2020 I’ve had the chance to work on a collection of glass plate negatives from amateur photographer Thomas W. Kennedy (active ca. 1890-1915). His photographs are a gem in the Seaport Museum’s collection since the majority of the 135 slides depict Lower Manhattan and the East River waterfront. Through Kennedy’s lens we see a city in the midst of tremendous change; there is a Manhattan skyline with no skyscrapers, and streets are filled with horse drawn carts. There are still sailing ships along the piers of South Street, but we know the final years of sail are on the horizon. Kennedy’s photographs capture elements of the late-nineteenth century port that would disappear within his lifetime.

Since the Thomas W. Kennedy Collection arrived at the Museum in 1969, the glass plate negatives and related modern prints have been a critical element when sharing with visitors how things used to be on South Street. The collection was even the focus of one the Museum’s first exhibitions and publication “South Street Around 1900: The Ships and Men of a Vanishing Way of Life Photographed by Thomas W. Kennedy”, which was installed on the Museum’s 1908 lightship Ambrose in 1970.

Despite being a celebrated part of the Museum’s collection for decades, the Kennedy’s glass plate negatives were not officially accessioned[1]The Alliance of American Museums defines accessioning as Accessioning is the formal act of legally accepting an object or objects to the category of material that a museum holds in the public trust, … Continue reading until 2016. After accessioning, each of the 135 negatives got their own record in our collections management database. Over the past months I’ve been updating these entries with exhibition notes from my predecessors, as well as with new research and metadata. During this new inventory process I’ve been drawn to the negatives that were not as thoroughly documented by past staff members; Kennedy’s street scenes and views of inland Manhattan have been the most rewarding to analyze, if only because it’s a relatively fresh angle for a well-known collection.

One aspect that’s been fun to look at is the variety of street advertising Kennedy captured in his photographs. Besides being fun to look at, these broadsides, building signs, and billboards tell us a lot about the businesses, consumer products, and entertainments of early 20th century New York City. Below I’ve picked a few of Kennedy’s photographs that have struck me during my inventory project, and what we can see (if really zoom in!)

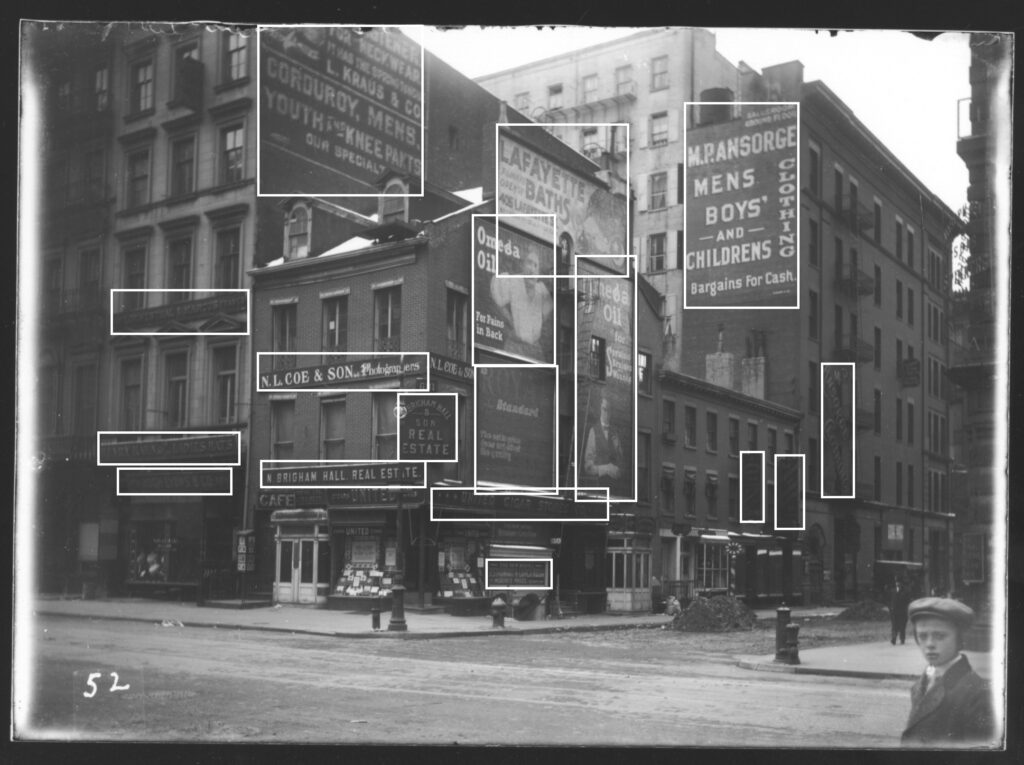

This photograph depicts the corner of Broadway and W. 3rd Street, and it is an example of a slide that can be looked over with a fine tooth comb. Below is the same photograph, but with each street advertisement and building sign outlined.

Here is a list of every business and product that I found legible: United Cigar Stores Co.; N. Brigham Hall & Son Real Estate; Hugh Lyons & Co.; Lowenthal & Marcus Frames; N.L. Coe & Son Photographers; L. Kraus & Co.; The Lafayette Baths; Omega Oil; The New Model Restaurant and Lunch Room (Moderate Prices); M.P. Ansorge Clothing; and Henry Kahn Ladies Hats.

From this list we could go in a number of different research directions; this image could be part of a larger story about industries like patent medicine and ladies millinery. No doubt a lot could be said about the design and font choices made for each advertisement. Though some businesses and products can only be found in a city directory or in passing mention in a trade journal, some businesses themselves are historically notable. In this photograph, the billboard for the Lafayette Baths at 405 Lafayette Street is arguably the most significant. The Lafayette Baths was one of the known gay bathhouses in 1910s New York City.[2] Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the Making of the Gay Male World by George Chauncey.

Unlike the previous photograph, this Kennedy slide only has visible street advertisements for one industry- passenger shipping. This photograph depicts the old “Steamship Row”, a row of brick houses that stood on the south side of Bowling Green that housed the offices of the likes of the Cunard Line, Red Star Line and French Line. The row was torn down during the construction of the Alexander Hamilton Custom House, which began in 1902 and was completed in 1907.

The advertising on this building is strictly for the shipping lines in the row.

What struck me about this photograph is that, along with conventional building signage for the Anchor Line visible on the nearest wall, the Anchor Line (and the neighboring American Line and Red Star Line offices) have suspended signs between the building’s chimneys.

The signs take advantage of the existing row house architecture to make the offices very, very visible.

This is one of the Kennedy shots that is both a waterfront view and includes a variety of billboards. This photograph was taken just south of the Wall Street Ferry slip—the Manhattan terminal for the Union Ferry Company route to Montague Street in Brooklyn.[3] Over & Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor by Brian J. Cudahy. pp. 226-230. Just as we see billboards and posters in the New York City subway stations today, the advertisements that lined the ferry slip were aimed at a captive audience of passengers. Thousands of commuters likely passed that poster for Dr. J. Fehr’s Talcum Powder.

East River piers that did not serve ferry routes did not have an exuberant number of advertisements. A 1903 film Panorama water front and Brooklyn Bridge from East River depicts the piers starting at about Broad Street and ends just south of Fulton Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. The film shows the Wall Street ferry slip (with a ferryboat) and distinct billboards.

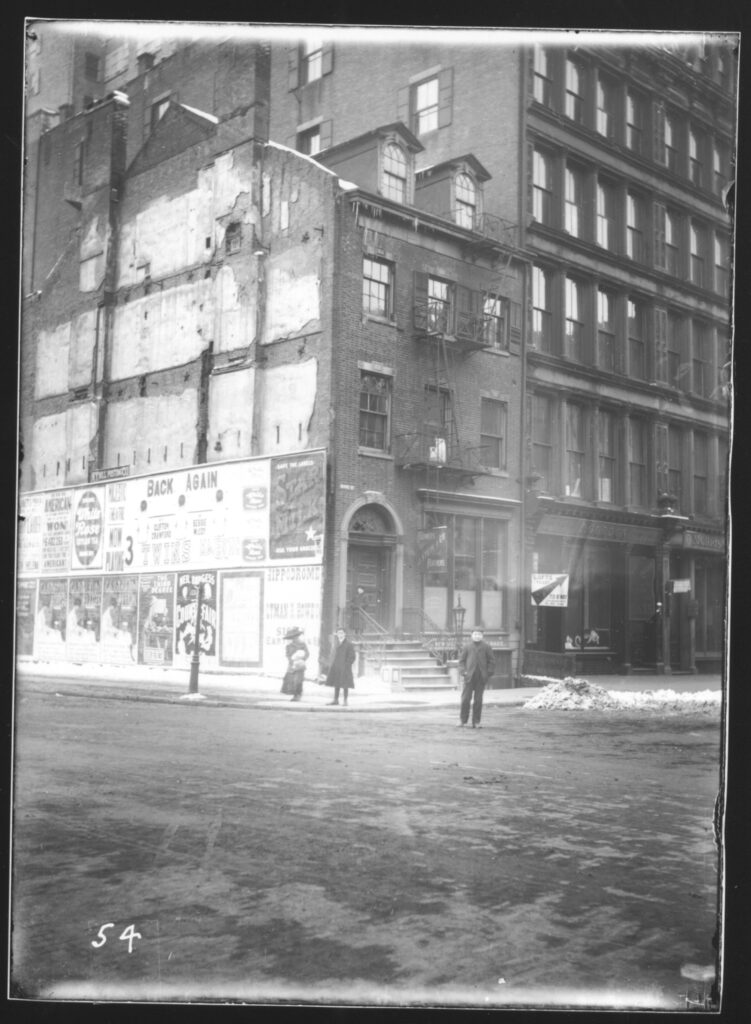

This photograph shows the corner of Bond Street and Lafayette Street with a wall purposely dedicated to advertising; the sign above the posters indicates it was managed by the N.Y. Bill Posting Company. Many of the legible posters are for beverage brands including Star Milk, White Rose Ceylon Tea, and Carnation Milk, but the most useful posters (from a cataloger’s point of view) are for theatre.

The three stage shows advertised on this wall are “The Third Degree”, “The County Fair” starring Neil Burgess, and “Three Twins” starring Clinton Crawford and Bessi McCoy at the Majestic Theatre. These posters can be used to date the photograph by cross referencing the shows’ runs on archives like the Internet Broadway Database or the Playbill Vault.

Though we’d only been able to date the photograph within Thomas Kennedy’s active years between ca. 1890-1915, these advertisements narrow it down to ca. 1909.

Along with stage shows, there is an advertisement for another form of entertainment that would take the 20th century by storm: film. The poster closest to the street corner is for film pioneer Lyman H. Howe’s “Sicily Earthquake” at the New York Hippodrome. The film depicted the destruction of Messina, Italy, during the renowned 1908 earthquake. One review from the showings at the Hippodrome said “It demonstrated the real possibilities of animated photography, in a way that was a revelation to the vast audience.”[4] The Moving Picture World, Volume 4. Chalmers Publishing Company, 1909, p. 145.

Not all advertisements were posted strictly where they were allowed. No doubt you’ve seen signs like “Post No Bills” which are meant to deter illegally placing posters on private property. However, closed storefronts and abandoned property have long been prime locations for “flyposting” as seen in this view of Watts and Hudson streets. The posters are concentrated on the building to the right which were, judging from the boarded up windows, unoccupied.

Like the previous photograph, a few of the legible posters are for theater and including “The Good Old Summertime” at 14th Street Theatre and “Babes in Toyland” at the Majestic Theatre. Again, with a little digging into Broadway archives, we can date this photo to ca. 1904.

One of the more interesting advertisements in this view is the poster for Sapolio soap near the street corner. Sapolio became a cautionary tale in business history about the importance of advertising. Sapolio had been one of the top soap brands in the United States, in part because of their innovative promotion since the brand’s founding in 1867.

In 1905 the company reduced its advertising budget, supposedly since they already controlled such a significant part of the market. Sales declined, the advertising budget was reduced even further, and Sapolio was believed for decades to be “a classic example of what happens when companies reduce advertising expenditures.”

This explanation has been challenged by economists (and the successors to the brand today) who say that the decline of Sapolio was from the brand’s unwillingness to innovate their product line.[5] A Re-Examination of the Causes of the Decline in Sales of Sapolio by Donald S. Tull. The Journal of Business April 1955, pp. 128-137.

This last photograph shows the crowd of people on Broad Street participating in the New York Curb Market, a stock market that was known for evading regulations and allowing New York Stock Exchange brokerages to informally trade in speculative securities.

Though “the Curb” could have a blog post in it’s own right (I suggest reading this post on The Gotham Center for New York City History), let me draw your attention to the road work being done on the right.

Some enterprising bill poster has decided that the wood barrels around the construction site were a good advertising opportunity.

After having the chance to catalog this incredible collection, Thomas Kennedy’s photographs are a reminder that our collections, even ones that have been at the Museum for nearly half-a-century, continue to hold fascinating details about early 20th century New York.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.

References

| ↑1 | The Alliance of American Museums defines accessioning as Accessioning is the formal act of legally accepting an object or objects to the category of material that a museum holds in the public trust, or in other words those in the museum’s permanent collection. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture and the Making of the Gay Male World by George Chauncey. |

| ↑3 | Over & Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor by Brian J. Cudahy. pp. 226-230. |

| ↑4 | The Moving Picture World, Volume 4. Chalmers Publishing Company, 1909, p. 145. |

| ↑5 | A Re-Examination of the Causes of the Decline in Sales of Sapolio by Donald S. Tull. The Journal of Business April 1955, pp. 128-137. |